Stephen King’s books have sold more than 350 million copies, many of which have been adapted into feature films, miniseries, television series, and comic books. King has published 58 fictional novels, and six non-fiction books. In his (more rare) non-fiction book, “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft” he gives his best advice to would be writers.

I like his conversational and transparent style in this book, you learn more about his writing life and his own (sometimes severe) hurdles. He shares his genius and–as usual–is super funny, I laughed out loud and took many notes throughout my reading.

King’s own synopsis of this book is: “On Writing is both a textbook for writers and a memoir of Stephen’s life and will, thus, appeal even to those who are not aspiring writers. If you’ve always wondered what led Steve to become a writer and how he came to be the success he is today, this will answer those questions.”

Where does King’s genius originate in his writing? A writer friend of mine concludes that “he doesn’t know jack, that he writes intuitively and that can’t be transferred. He can only say, “This is how I write.” She says if you follow his advice, you will probably end up sounding a lot like Stephen King. I do agree that he is an extraordinary “gut-centered” writer, which my book discusses. But his other two creativity centers: His head and heart center are actively working too–creating striking intersections!

I happen to heartily disagree with my writer friend on the value of King’s advice. I get inspired by his book–it made me ponder exceptions to his rules, which I’ll highlight below. I ask writers out there–did you benefit from King’s writing instructions–or not?

Along with his writing rules, King chronicles his career as a writer (starting in grade school), which is wonderfully entertaining, scary and down to earth–just like his novels. His rules follow:

Rule #1: Don’t use passive voice

Active voice is great if you want to produce a driving passage, filled with energy and momentum. This rule got me thinking… its not always true! What if we want to convey something else – mystery, suspense? Here is an example of passive voice:

“The body was hanging in the hall. It had been hung there some time in the night, when we were sleeping. As we made our way down to breakfast, we all stepped around it. Nobody looked up. We all knew who it was.”

If we use an active voice: “Somebody hung it in the night,” it doesn’t have the same feeling. The focus here is on the body. Using passive voice increases the tension and forces us to wonder, “Who hung it there?”

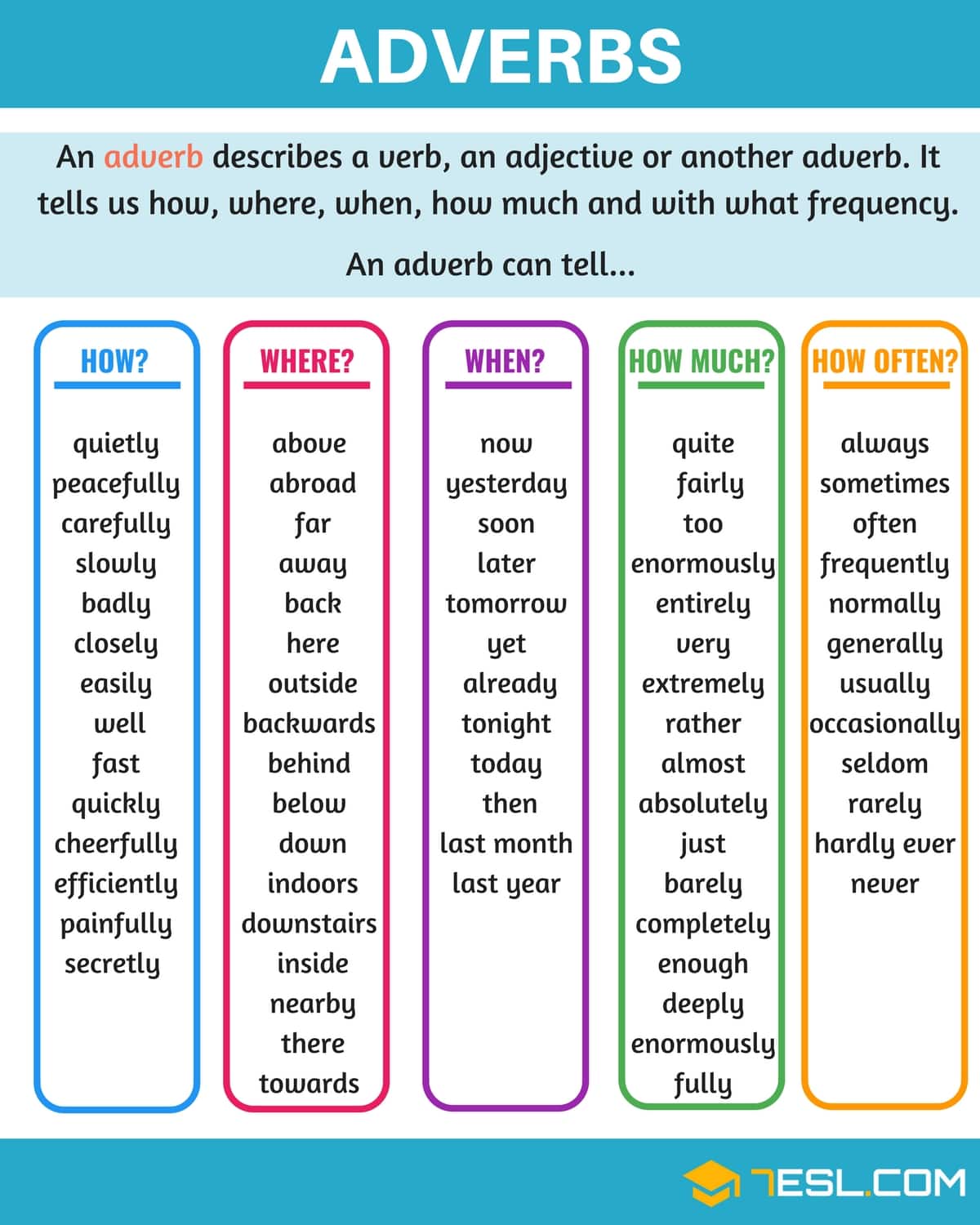

Stephen King’s Rule #2: Don’t use adverbs

I agree with King that the overuse of adverbs (anything ending in -ly) is mostly annoying and unneccessary. I’m trying hard to avoid them in my own writing. However, sometimes an adverb can fulfill a purpose. Sometimes we need to describe how someone is performing an action, without a lengthy descriptive phrase.

“Gently, oh so gently, they lifted my body out of the river. They placed it on the bank and arranged my tattered clothing to cover what remained of my flesh. Then they stood around me, in perfect silence, their hats in their hands. If only they had shown me such respect when I was alive.”

This passage could have begun without “gently.” But the impact of the (dead) narrator’s voice would have been compromised, and the force of the final line would have been diminished.

Stephen King’s Rule #3: Don’t use a long word when you can use a short one

English is a mashup of Germanic and Latin roots (among other things). The Germanic lexicon is agglomerative: get up, get down. Latin roots are inflected: ascend, descend. Academic writing favors Latin roots, while colloquial speech prefers the Germanic. If you want to sound like Hemingway, or Stephen King, stick to the Germanic roots. But, if you are after a more scholarly effect, go for the Latin.

In dialogue anything is permissible. Sometimes I do believe a five-dollar word can accomplish more than its one-syllable equivalent. Here is the last phrase of Camus’ The Stranger, taken from two different translations: Which version will you remember?

“… they greet me with cries of hate.”

“… they greet me with howls of execration.”

This example shows you can write anything, if you can pull it off. If you can’t, then like Kings says, don’t do it! Being able to do something successfully is what is important, not whether you follow “the rules”.

It is important to understand the difference between commercial and literary fiction, which can be subtle. In general, commercial fiction is formulaic, whereas literary fiction tends to experiment with form and style. Commercial fiction falls into genres – science fiction, chick lit, romance, etc. – whereas literary fiction may cross or blend genres, or depart from them entirely. Literary fiction also places greater value on the craft of writing, which is not to say that genre fiction does not, but in the case of literary fiction, the writing is front and center.

I get a big kick out of King’s editing style, he is a strict (former) English teacher: This example shows you CAN use hyphens, commas, etc. extensively AND use long sentences: “Writing did not save my life–Dr. David Brown’s skill and my wife’s loving care did that–but it has continued to do what is always has done: it makes my life a brighter and more pleasant place.

There are at least five big ideas that King shares: 1) Embrace rejection: He craved feedback from publishers who rejected him. He had a ‘growth mindset’, not a ‘fixed mind set’. Fail faster to succeed. 2) On muses: Show up every day, “work your ass off” you must clock in your time if you want your muse to show up 3) You must read and write–both!–a lot. He reads 70-80 books a year (only after he clocks in his own daily writing). 4) Jumper cable brain: Must learn to settle your brain down to write. To be truly creative we can only do one thing at a time (I explain the science behind this in my book), so turn your phone off and get into your writing cave! 5) He did not write one word of any of his books for money. (If there was one person he wanted to impress, that would only be his fellow-writer wife). He writes purely for the JOY of it, the money is only a by-product of his writing craft. He writes for the joy of creation!

I love this book and think you will too. What do you think about his rules and ideas? Where do you see exceptions?

Andrey says: “I used to work in theatre which was a big help when it came to making props…”

Andrey says: “I used to work in theatre which was a big help when it came to making props…”